Most of all, this book about a race, which was the last great

expedition that ended the Age of Discovery, is a study in leadership.

Paul Théroux

It is the man that matters, here as everywhere.

Fridtjof Nansen

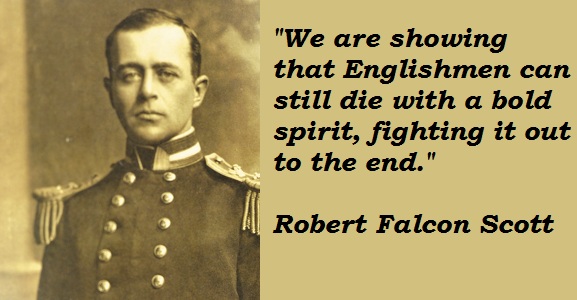

The last place on earth est un livre écrit par Roland Huntford sur la course au pôle sud entre Amundsen et Scott. Pour ceux qui ne se rappelleraient pas leurs livres scolaires, le pôle sud fut le dernier grand lieu de conquête de la planète, et fut ainsi l'objet d'une opposition restée célèbre entre deux personalités totalement opposées: Robert Falcon Scott, un capitaine de la Navy britannique, et Roald Amundsen, un marin et explorateur norvégien. Amundsen atteignit le pôle sud le 19 décembre 1911, batit Scott d'un mois, et surtout ramena l'ensemble de son expédition sans aucune perte humaine, là où Scott périt avec quatre de ses compagnons. Dans l'imaginaire britannique, Scott est longtemps resté le parfait héros de l'empire, courageux jusqu'au sacrifice, alors que la victoire d'Amundsen n'avait été possible, suivant l'expression de certains membres de la Royal Geographic Society, que grace à des "dirty tricks" (coups tordus).

Le livre de Huntford, publié à la fin des années 70, créa une grande polémique en Grande-Bretagne, en déconstruisant le mythe héroïque Scottien. Pour Huntford, le succès d'Amundsen était la victoire d'un passioné mieux préparé, connaissant parfaitement le terrain polaire, maitrisant les différentes techniques de ski sur neige et l'utilisation de chiens de traineau, là où Scott n'était finalement qu'un capitaine de marine anglais dévoré par l'ambition, lancé dans une course à la célébrité et à l'avancement.

Plusieurs livres ont été écrit depuis pour défendre Robert Scott, dont Captain Scott de Ranulph Fiennes, et The coldest march de Susan Solomon. Même si certains de ces livres apportent quelques éléments nouveaux, ou réfutent certains points relativement mineurs des thèses de Huntford, on ressort de l'ensemble de ces lectures convaincu; Amundsen avait consacré sa vie à l'exploration polaire. Il était allé apprendre chez les inuits l'utilisation des vêtements amples en fourrures, faits d'une seule pièce, qui limitaient la perte de chaleur et maitrisaient l'évacuation de la transpiration.

Il avait aussi appris à utiliser les chiens de traineau et était un skieur de fond entrainé depuis son enfance, qui avait de plus parfait sa technique de "fartage" (en fait la création d'une fine couche glacée sous les skis) au cours de ses différents voyages.

Il créa un petit groupe comprenant en particulier un skieur et alpiniste de très haut niveau (Olav Bjaaland), dont la compétence fut un des atouts majeurs de la réussite de l'expédition.

De son côté Scott ne s'intéressa à l'exploration polaire que tardivement dans sa vie, parce qu'il y vit surtout un moyen de faire avancer sa carrière d'officier de la Navy. Il refusa d'utiliser les skis et les chiens de traineau, préférant la marche et l'utilisation des poneys (qui moururent tous, faute d'une adaptation correcte au froid et d'une nourriture appropriée). La course des anglais vers le pôle dût se faire en tirant les traineaux à la force des jarrets.

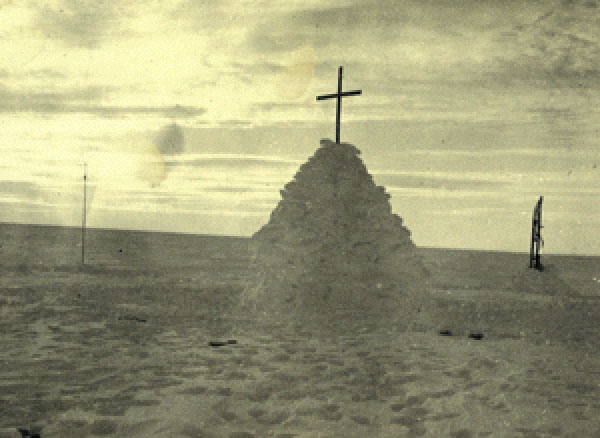

Les dépots de nourriture furent insuffisamment marqués, les ordres donnés de façon désordonnée et insuffisamment claire. Le choix des hommes qui participèrent à la course finale fut malheureux; l'un d'entre eux, officier de cavalerie venu pour s'occuper des poneys, souffrait des séquelles d'une grave blessure à la hanche contractée lors de la guerre des Boers. Scott ajouta au dernier moment une personne supplémentaire, sans prévoir les rations alimentaires suffisantes. Scott et ses compagnons moururent de faim, de froid et de fatigue lors de leur voyage de retour vers leur camp de base.

Le livre est la démonstration qu'un petit groupe soudé, compétent et

efficace peut réussir là où une organisation lourde et rigide

comme l'était la

marine britannique de l'ère Edwardienne ne parvint finalement qu'à un

désastre. Les britanniques avaient déjà eu l'occasion de

mesurer le travail qu'ils devaient faire après

l'expédition Franklin de 1845, expédition qui devait trouver le

passage du Nord-Ouest. Elle s'était déjà soldée par un désastre, les

128 hommes mourant tous de faim et de maladie (botulisme, accumulation

de plomb, scorbut, ...) alors qu'à côté d'eux les populations

indigènes inuits vivaient dans une relative abondance.

Pourtant les britanniques ne furent jamais capables de tirer les

enseignements de leurs échecs, même lorsque John Rae, un explorateur

canadien utilisant déjà les techniques inuits, rapporta la nouvelle de

la mort de tous les membres de l'expédition Franklin en 1848. Engoncés

dans leurs certitudes et leurs discours, incapables de comprendre, et

même d'essayer de comprendre la réalité du terrain, ils persistèrent

dans leurs erreurs. Comme Scott plus tard, Franklin fut

présenté comme un héros alors qu'il avait tout de même tué 128

personnes.

Il n'y eut jamais la moindre remise en question des

méthodes employées. Pire, lors du choix de Scott pour mener

l'expédition britannique, le Times écrivit:

Although Scott has no polar experience, that is a small matter; any

competent young officer will soon make himself familiar with what has

been done and what remains to do. [Bien que Scott n'ait aucune

expérience de l'exploration polaire, c'est de peu d'importance;

n'importe quel jeune officier compétent saura rapidement se mettre au

courant de ce qui a été fait et de ce qui reste à faire.]

Il y eut bien quelques esprits chagrins qui s'étonnèrent du manque de compétence de Scott pour mener une expédition aussi technique, mais ils furent vite réduits au silence, accusés "d'attaquer la Navy", alors qu'ils s'efforçaient simplement d'exprimer la voix du bon sens et demandaient simplement de tirer les (nombreuses) leçons du passé...

"The Arctic Council planning a search for Sir John Franklin" by

Stephen Pearce

Entre 1850 et 1854, l'expédition britannique McClure avait elle aussi failli mourir dans les mêmes circonstances que l'expédition Franklin et n'avait du son salut qu'à des secours venus en traineau.

C'est finalement Amundsen qui fut le premier à naviguer le passage du Nord Ouest entre 1903 et 1906, où il apprit d'ailleurs à peaufiner sa préparation aux contacts des inuits.

Pour ceux qui, comme moi, furent éduqués en partie dans la culture anglaise, Scott avait toujours été présenté dans mon enfance comme le héros par excellence, allant jusqu'au sacrifice de sa vie pour atteindre son but, là où Amundsen était vu comme une sorte de "bad guy", trompant Scott jusqu'au dernier moment en faisant croire qu'il partait pour le nord et non pour le sud (en dehors de l'aspect tactique, Amundsen avait aussi de sérieux problèmes financiers, et il savait qu'annoncer une expédition vers le pôle sud ne lui permettrait pas de trouver des financements). On peut donc s'interroger sur le décalage entre la réalité et la représentation que l'on en avait encore dans les années 70.

Il ne faut pas aller chercher bien loin. Scott avait consacré une grande partie de ses efforts à se rendre visible, écrivant beaucoup, et avec un vrai talent. Il avait un art consommé pour dramatiser ses aventures; une comparaison des textes d'Amundsen et de Scott montre en particulier que le premier prenait en permanence des marges de sécurité, et anticipait les problèmes qui pouvaient se présenter. Pour Scott, quatre jours de froid et de brouillard étaient une épreuve qu'il fallait surmonter avec courage. Pour Amundsen, c'était quatre jours de mauvais temps. Amundsen arriva 39 jours avant Scott au pôle Sud, en couvrant des distances journalières bien plus importantes, et retourna à son camp de base sans perdre un homme.

Ce qui transforma un désastre en exploit fut donc la communication de

l'empire britannique face à la Norvège, le talent de conteur de Scott

face à la rédaction plate et sèche d'Amundsen, le verbe contre les

faits. Il faudra attendre

presque 70 ans pour que la vérité soit rétablie, et il existe encore

aujourd'hui bien plus de livres, de travaux universitaires ou de sites

web consacrés à Scott qu'à Amundsen.

Bien entendu, Scott ne

saurait porter seul la responsabilité de son échec: il

était avant tout le produit et le représentant d'un système de

classe, hiérarchisé et rigide à l'extrême. Il avait agi simplement comme on

l'attendait de lui, et ce jusqu'à la fin; s'il avait été choisi, c'est

parce qu'il

était adapté à la tâche qu'on lui confiait, relativement au

système de valeurs de l'empire britannique de la fin du XIXème

siècle. Il aura à en subir à la fois l'excès d'honneur et

l'indignité. Et si la polémique prit une telle ampleur, c'est parce

qu'elle remettait en cause un système encore plus qu'un homme.

The pen is mightier than the sword disent nos amis britanniques tant il est vrai qu'aujourd'hui peut être plus qu'hier encore, le principe de réalité à laissé la place au champ du discours comme vérité alternative. Mais si en environnement extrême le principe de réalité tue rapidement, il tue aussi en d'autres circonstances; il y prend simplement d'autres formes et prend seulement plus de temps.

How like him and the whole expedition is his telegram home - as simple

and straightforward as if it concerned a holiday tour in the

mountains. It speaks of what is achieved, not of their

hardships. That is the mark of the right man,

quiet and strong.

Fridtjof Nansen

On February 10, 1911, we started for the South to establish depots, and continued our journey until April 11. We formed three depots and stored in them 3 tons of provisions, including 22 hundredweight of seal meat. As there were no landmarks, we had to indicate the position of our depots by flags, which were posted at a distance of about four miles to the east and west. The first barrier afforded the best going, and was specially adapted for dog-sledging. Thus, on February 15 we did sixty-two miles with sledges. Each sledge weighed 660 pounds, and we had six dogs for each. The upper barrier ("barrier surface") was smooth and even. There were a few crevasses here and there, but we only found them dangerous at one or two points. The barrier went in long, regular undulations. The weather was very favourable, with calms or light winds. The lowest temperature at this station was -49° F., which was taken on March 4.

When we returned to winter quarters on February 5 from a first trip, we found that the Fram had already left us. With joy and pride we heard from those who had stayed behind that our gallant captain had succeeded in sailing her farther south than any former ship. So the good old Fram has shown the flag of Norway both farthest north and farthest south. The most southerly latitude reached by the Fram was 78° 41'.

Before the winter set in we had 60 tons of seal meat in our winter quarters; this was enough for ourselves and our 110 dogs. We had built eight kennels and a number of connecting tents and snow huts. When we had provided for the dogs, we thought of ourselves. Our little hut was almost entirely covered with snow. Not till the middle of April did we decide to adopt artificial light in the hut. This we did with the help of a Lux lamp of 200 candle-power, which gave an excellent light and kept the indoor temperature at about 68° F. throughout the winter. The ventilation was very satisfactory, and we got sufficient fresh air. The hut was directly connected with the house in which we had our workshop, larder, storeroom, and cellar, besides a single bathroom and observatory. Thus we had everything within doors and easily got at, in case the weather should be so cold and stormy that we could not venture out.

The sun left us on April 22, and we did not see it again for four months. We spent the winter in altering our whole equipment, which our depot journeys had shown to be too heavy and clumsy for the smooth barrier surface. At the same time we carried out all the scientific work for which there was opportunity. We made a number of surprising meteorological observations. There was very little snow, in spite of there being open water in the neighbourhood. We had expected to observe higher temperatures in the course of the winter, but the thermometer remained very low. During five months temperatures were observed varying between -58° and -74° F. We had the lowest (-74° F.) on August 13; the weather was calm. On August 1 we had -72° F. with a wind of thirteen miles an hour. The mean temperature for the year was -15° F. We expected blizzard after blizzard, but had only two moderate storms. We made many excellent observations of the aurora australis in all parts of the heavens. Our bill of health was the best possible throughout the whole winter. When the sun returned on August 24 it shone upon men who were healthy in mind and body, and ready to begin the task that lay before them.

We had brought the sledges the day before to the starting-point of the southern journey. At the beginning of September the temperature rose, and it was decided to commence the journey. On September 8 a party of eight men set out, with seven sledges and ninety dogs, provisioned for ninety days. The surface was excellent, and the temperature not so bad as it might have been. But on the following day we saw that we had started too early. The temperature then fell, and remained for some days between -58° and -75° F. Personally we did not suffer at all, as we had good fur clothing, but with the dogs it was another matter. They grew lanker and lanker every day, and we soon saw that they would not be able to stand it in the long run. At our depot in lat. 80° we agreed to turn back and await the arrival of spring. After having stored our provisions, we returned to the hut. Excepting the loss of a few dogs and one or two frostbitten heels, all was well. It was not till the middle of October that the spring began in earnest. Seals and birds were sighted. The temperature remained steady, between -5° and -22° F.

Meanwhile we had abandoned the original plan, by which all were to go to the south. Five men were to do this, while three others made a trip to the east, to visit King Edward VII. Land. This trip did not form part of our programme, but as the English did not reach this land last summer, as had been their intention, we agreed that it would be best to undertake this journey in addition.

On October 20 the southern party left. It consisted of five men with four sledges and fifty-two dogs, and had provisions for four months. Everything was in excellent order, and we had made up our minds to take it easy during the first part of the journey, so that we and the dogs might not be too fatigued, and we therefore decided to make a little halt on the 22nd at the depot that lay in lat. 80°. However, we missed the mark owing to thick fog, but after two or three miles' march we found the place again.

When we had rested here and given the dogs as much seal meat as they were able to eat, we started again on the 26th. The temperature remained steady, between -5° and -22° F.

At first we had made up our minds not to drive more than twelve to eighteen miles a day; but this proved to be too little, thanks to our strong and willing animals. At lat. 80° we began to erect snow beacons, about the height of a man, to show us the way home.

On the 31st we reached the depot in lat. 81°. We halted for a day and fed the dogs on pemmican. On November 5 we reached the depot in 82°, where for the last time the dogs got as much to eat as they could manage.

On the 8th we started southward again, and now made a daily march of about thirty miles. In order to relieve the heavily laden sledges, we formed a depot at every parallel we reached. The journey from lat. 82° to 83° was a pure pleasure trip, on account of the surface and the temperature, which were as favourable as one could wish. Everything went swimmingly until the 9th, when we sighted South Victoria Land and the continuation of the mountain chain, which Shackleton gives on his map, running southeast from Beardmore Glacier. On the same day we reached lat. 83°, and established here Depot No. 4.

On the 11th we made the interesting discovery that the Ross Barrier ended in an elevation on the south-east, formed between a chain of mountains running south-eastward from South Victoria Land and another chain on the opposite side, which runs south-westward in continuation of King Edward VII. Land.

On the 13th we reached lat. 84°, where we established a depot. On the 16th we got to 85°, where again we formed a depot. From our winter quarters at Framheim we had marched due south the whole time.

On November 17, in lat. 85°, we came to a spot where the land barrier intersected our route, though for the time being this did not cause us any difficulty. The barrier here rises in the form of a wave to a height of about 300 feet, and its limit is shown by a few large fissures. Here we established our main depot. We took supplies for sixty days on the sledges and left behind enough provisions for thirty days.

The land under which we now lay, and which we were to attack, looked perfectly impossible, with peaks along the barrier which rose to heights of from 2,000 to 10,000 feet. Farther south we saw more peaks, of 15,000 feet or higher.

Next day we began to climb. The first part of the work was easy, as the ground rose gradually with smooth snow-slopes below the mountain-side. Our dogs working well, it did not take us long to get over these slopes.

At the next point we met with some small, very steep glaciers, and here we had to harness twenty dogs to each sledge and take the four sledges in two journeys. Some places were so steep that it was difficult to use our ski. Several times we were compelled by deep crevasses to turn back.

On the first day we climbed 2,000 feet. The next day we crossed small glaciers, and camped at a height of 4,635 feet. On the third day we were obliged to descend the great Axel Heiberg Glacier, which separates the mountains of the coast from those farther south.

On the following day the longest part of our climbing began. Many detours had to be made to avoid broad fissures and open crevasses. Most of them were filled up, as in all probability the glacier had long ago ceased to move; but we had to be very careful, nevertheless, as we could never know the depth of snow that covered them. Our camp that night was in very picturesque surroundings, at a height of about 5,000 feet.

The glacier was here imprisoned between two mountains of 15,000 feet, which we named after Fridtjof Nansen and Don Pedro Christophersen.

At the bottom of the glacier we saw Ole Engelstad's great snow-cone rising in the air to 19,000 feet. The glacier was much broken up in this narrow defile; enormous crevasses seemed as if they would stop our going farther, but fortunately it was not so bad as it looked.

Our dogs, which during the last few days had covered a distance of nearly 440 miles, put in a very good piece of work that day, as they did twenty-two miles on ground rising to 5,770 feet. It was an almost incredible record. It only took us four days from the barrier to reach the immense inland plateau. We camped at a height of 7,600 feet. Here we had to kill twenty-four of our brave dogs, keeping eighteen - six for each of our three sledges. We halted here for four days on account of bad weather. On November 25 we were tired of waiting, and started again. On the 26th we were overtaken by a raging blizzard. In the thick, driving snow we could see absolutely nothing; but we felt that, contrary to what we had expected - namely, a further ascent - we were going rapidly downhill. The hypsometer that day showed a descent of 600 feet. We continued our march next day in a strong wind and thick, driving snow. Our faces were badly frozen. There was no danger, but we simply could see nothing. Next day, according to our reckoning, we reached lat. 86°. The hypsometer showed a fall of 800 feet. The following day passed in the same way. The weather cleared up about noon, and there appeared to our astonished eyes a mighty mountain range to the east of us, and not far away. But the vision only lasted a moment, and then disappeared again in the driving snow. On the 29th the weather became calmer and the sun shone - a pleasant surprise. Our course lay over a great glacier, which ran in a southerly direction. On its eastern side was a chain of mountains running to the southeast. We had no view of its western part, as this was lost in a thick fog. At the foot of the Devil's Glacier we established a depot in lat. 86° 21', calculated for six days. The hypsometer showed 8,000 feet above sea level. On November 30 we began to ascend the glacier. The lower part was much broken up and dangerous, and the thin bridges of snow over the crevasses often broke under us. From our camp that evening we had a splendid view of the mountains to the east. Mount Helmer Hansen was the most remarkable of them all; it was 12,000 feet high, and covered by a glacier so rugged that in all probability it would have been impossible to find foothold on it. Here were also Mounts Oskar Wisting, Sverre Hassel, and Olav Bjaaland, grandly lighted up by the rays of the sun. In the distance, and only visible from time to time through the driving mists, we saw Mount Thorvald Nilsen, with peaks rising to 15,000 feet. We could only see those parts of them that lay nearest to us. It took us three days to get over the Devil's Glacier, as the weather was unusually misty.

On December 1 we left the glacier in high spirits. It was cut up by innumerable crevasses and holes. We were now at a height of 9,370 feet. In the mist and driving snow it looked as if we had a frozen lake before us; but it proved to be a sloping plateau of ice, full of small blocks of ice. Our walk across this frozen lake was not pleasant. The ground under our feet was evidently hollow, and it sounded as if we were walking on empty barrels. First a man fell through, then a couple of dogs; but they got up again all right. We could not, of course, use our ski on this smooth-polished ice, but we got on fairly well with the sledges. We called this place the Devil's Ballroom. This part of our march was the most unpleasant of the whole trip. On December 2 we reached our greatest elevation. According to the hypsometer and our aneroid barometer we were at a height of 11,075 feet - this was in lat. 87° 51'. On December 8 the bad weather came to an end, the sun shone on us once more, and we were able to take our observations again. It proved that the observations and our reckoning of the distance covered gave exactly the same result - namely, 88° 16' S. lat. Before us lay an absolutely flat plateau, only broken by small crevices. In the afternoon we passed 88° 23', Shackleton's farthest south. We pitched our camp in 88° 25', and established our last depot - No. 10. From 88° 25' the plateau began to descend evenly and very slowly. We reached 88° 29' on December 9. On December 10, 88° 56'; December 11, 89° 15'; December 12, 89° 30'; December 13, 89° 45'.

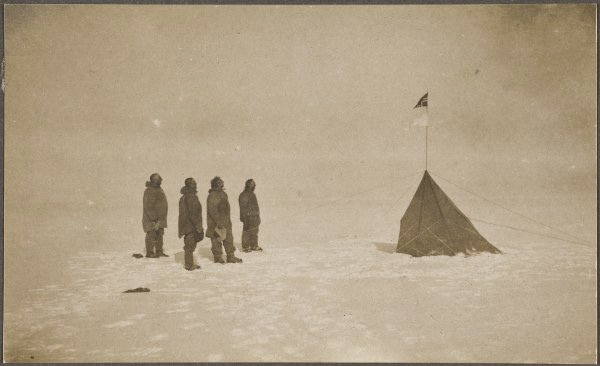

Up to this moment the observations and our reckoning had shown a surprising agreement. We reckoned that we should be at the Pole on December 14. On the afternoon of that day we had brilliant weather - a light wind from the south-east with a temperature of -10° F. The sledges were going very well. The day passed without any occurrence worth mentioning, and at three o'clock in the afternoon we halted, as according to our reckoning we had reached our goal.

We all assembled about the Norwegian flag - a handsome silken flag - which we took and planted all together, and gave the immense plateau on which the Pole is situated the name of "King Haakon VII.'s Plateau."

It was a vast plain of the same character in every direction, mile after mile. During the afternoon we traversed the neighbourhood of the camp, and on the following day, as the weather was fine, we were occupied from six in the morning till seven in the evening in taking observations, which gave us 89° 55' as the result. In order to take observations as near the Pole as possible, we went on, as near true south as we could, for the remaining 9 kilometres. On December 16 we pitched our camp in brilliant sunshine, with the best conditions for taking observations. Four of us took observations every hour of the day - twenty-four in all. The results of these will be submitted to the examination of experts.

We have thus taken observations as near to the Pole as was humanly possible with the instruments at our disposal. We had a sextant and artificial horizon calculated for a radius of 8 kilometres.

On December 17 we were ready to go. We raised on the spot a little circular tent, and planted above it the Norwegian flag and the Fram's pennant. The Norwegian camp at the South Pole was given the name of "Polheim." The distance from our winter quarters to the Pole was about 870 English miles, so that we had covered on an average 15 1/2 miles a day.

We began the return journey on December 17. The weather was unusually favourable, and this made our return considerably easier than the march to the Pole. We arrived at "Framheim," our winter quarters, in January, 1912, with two sledges and eleven dogs, all well. On the homeward journey we covered an average of 22 1/2 miles a day. The lowest temperature we observed on this trip was -24° F., and the highest +23° F.

The principal result - besides the attainment of the Pole - is the determination of the extent and character of the Ross Barrier. Next to this, the discovery of a connection between South Victoria Land and, probably, King Edward VII. Land through their continuation in huge mountain-ranges, which run to the south-east and were seen as far south as lat. 88° 8', but which in all probability are continued right across the Antarctic Continent. We gave the name of "Queen Maud's Mountains" to the whole range of these newly discovered mountains, about 530 miles in length.

The expedition to King Edward VII. Land, under Lieutenant Prestrud, has achieved excellent results. Scott's discovery was confirmed, and the examination of the Bay of Whales and the Ice Barrier, which the party carried out, is of great interest. Good geological collections have been obtained from King Edward VII. Land and South Victoria Land.

The Fram arrived at the Bay of Whales on January 9, having been delayed in the "Roaring Forties " by easterly winds.

On January 16 the Japanese expedition arrived at the Bay of Whales, and landed on the Barrier near our winter quarters.

We left the Bay of Whales on January 30. We had a long voyage on account of contrary wind.

We are all in the best of health.

Roald Amundsen.

Hobart,

March 8, 1912.

Le téléchargement ou la reproduction des documents et photographies

présents sur ce site sont autorisés à condition que leur origine soit

explicitement mentionnée et que leur utilisation

se limite à des fins non commerciales, notamment de recherche,

d'éducation et d'enseignement.

Tous droits réservés.

Dernière modification: 09:48, 22/02/2024